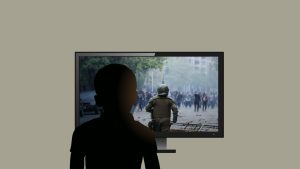

Violence in movies, television, and video games has long been a concern for parents, but the events at the nation’s Capitol, the responses to the Black Lives Matter protests, and exhibitions of police brutality, have served as a visceral reminder that children are frequently exposed to violent and graphic images on the news and in their social media feeds as well. Studies show that some children have problems processing this exposure, which can lead to both short- and long-term effects in kids, who risk being desensitized or developing aggressive attitudes or behavior over time. Furthermore, as a result of the pandemic, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of hours children and teens engage in video game play.

Many of these games reward highly violent, sexualized, prejudiced, and aggressive behavior; these first-hand experiences are likely consequential for future behavior and ideals. Every child is unique in the way that they react to the violence they see onscreen and some children are more susceptible than others, so it’s important for parents to monitor both what their children are watching and playing, as well as how it affects them. In addition, an open dialogue about the content they are consuming is key to establishing digital wellness. Furthermore, as Dr. Brad Bushman, PhD, Professor of Communication & Rinehart Chair of Mass Communication at Ohio State University says, “the effects of harmful media exposure are not always visible to the naked eye. For example, one cannot see what harmful media is doing to the brain or to thoughts and attitudes.” Because these concerns are so top of mind for parents, Children and Screens invited many of the leading figures in the fields of public health, education, psychology, and parenting to weigh in with their suggestions below on the best ways to address violent media. The size and significance of the impact of media violence from decades of vast psychological research from top academic institutions has recently been hotly debated. We continue to see an ever-increasing thirst for violence in entertainment media and exposure to violent pornography, and differential media effects in different children. While we recognize limitations in the generalizability of laboratory research to real-life situations and that most children who are playing violent video games aren’t perpetrating real-life violence, there continues to be questions about gaming’s impacts and a large void in longitudinal and naturalistic research studies which employ the latest novel technologies and methodologies. We believe that further research is warranted that is not influenced by the gaming or media industries. As such, the advice included in this resource is completely independent and intended to be carefully considered within each reader’s family context.

Digital Diet

Most parents keep an eye on the foods their children eat, encouraging them to fuel their bodies with a healthy, balanced diet. However, many families fail to monitor children’s media intake with the same diligence. “Media characters often engage in unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, taking drugs, having casual and unprotected sex, using profanity, and behaving in an aggressive and violent manner,” says Dr. Bushman. “Parents should be just as concerned about the media their children consume as the food they consume, and they should make sure their children follow a healthy diet in all regards.”

“In order to support your children’s development, prevent them from watching violent TV shows and playing violent video games, especially if the violent characters and avatars are heroic, liked by the child, appear to be doing it for good causes, or are rewarded for violent behavior,” echoes L. Rowell Huesmann, Director of the Aggression Research Program at the University of Michigan. “If your children do view these media, discuss with them how this is not the way good people should act, and that they don’t want to imitate such behavior.”

Tom Hummer, Assistant Research Professor at Indiana University School of Medicine, agrees that parents can play a key role in helping their kids choose prosocial games. “Violent video games often reward impulsive, aggressive reactions, so especially at younger ages, and with more impulsive children, parents can promote video games that require cooperation and engage critical thinking.” As teens mature, they learn how to regulate emotions and behaviors and seek out emotional and social support online. “Parents should acknowledge the importance and positive impact these outlets can have, while also empowering teens to recognize harmful influences that inhibit their development of healthy coping skills,” Hummer adds.

One way to monitor your children’s media diet is to have regular conversations about what they’re watching. “Ask for their opinions and share yours, too,” says Amy Nathanson, PhD, Ohio State University Professor of Communication. “With younger children, it’s best to be direct: tell them if you don’t like the content they’re watching and explain why. This strategy might not work as well as children mature, so if you’re dealing with older kids and teens, ask questions that will encourage them to apply critical thinking skills to evaluate the content they’re consuming.”

Changing Brains

According to Douglas A. Gentile, PhD, Psychology Professor at Iowa State University, there are approximately 19 scientifically documented effects that exposure to media violence can have, some immediate and some long-term. “We can boil these effects down to the following: viewing media violence changes the way children perceive the world and the way they think. It’s not about causing school shootings,” says Gentile. “It’s far more subtle than that, which makes it hard to notice the effect because it happens inside the ‘black box.’ For example, we won’t notice becoming desensitized because it’s a process that happens slowly over a long period of time.” The good news, Gentile assures us, is that we can always work to become re-sensitized. “The brain is plastic,” he explains, “which means it can change to support being more caring, compassionate, and kind.”

Be a Media Model

Kids are often more perceptive than we realize, and they’ll pick up behaviors and habits from their environment. “Model the behavior you want to see in your child,” says James Densley, PhD, professor of Criminal Justice at Metropolitan State University. “If you’re doomscrolling in the bedroom or rage tweeting from the dinner table, you can expect your kids to do the same.”

It’s important to remember that it’s not just our behavior that children will pick up on, but the behaviors they see onscreen, as well. “Media can present attractive role models, whose behavior is often rewarded by success and social approval,” says Barbara Krahé, Professor, Social Psychologist, and Media Violence Researcher at the University of Potsdam. “Exactly what viewers of any age learn from the media they consume depends on the content they see. If they watch violent action, this may promote aggressive behavior; if they see helping behavior, they may become more prosocial themselves.”

Mediator and Digital Health Expert Gwenn S. Okeeffe, MD, JD, points out that “even though we can’t escape media violence completely, we can help our kids minimize its impact.” In addition to leading by example by avoiding media violence in their own media use, Okeeffe recommends that parents embrace unplugged family time. “Screen free time is one of the best ways to build self-esteem, resiliency and buffer the negative hits of media violence,” she explains.

Don’t be Fooled

The entertainment industry knows that violence attracts audiences, and over the years, they’ve found ways to package that violence to make it appear less harmful to parents. “Our research has shown that a lot of the violence in PG-13 movies is perpetrated by virtuous characters who use it in defense of friends and family,” says Dan Romer, PhD, Research Director at University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center. “This makes it appear morally justified and less objectionable to parents. By omitting the bloody effects of violence, it also allows the movie industry’s review board to give movies with lots of violence the coveted PG-13 rating.” Romer suggests that parents should consider more than just the rating when determining whether a movie or TV show is appropriate for their child, especially the use of firearms. “Young people are particularly prone to injuries involving guns,” he explains, “and showing their use for heroic purposes in screen media could risk imitation.”

When in Doubt, Turn it Off

Many parents falsely assume that young children aren’t paying attention to the news if it’s on nearby while they play, or that they can’t understand it even if they do notice, but research has shown that TV news playing in the background has roughly the same impact on young children’s sleep at night as sitting and watching a violent movie or show. “Researchers have found that the violence in TV news can contribute to children’s sense that their environment isn’t safe,” says Michelle M. Garrison, PhD, Associate Professor at the University of Washington. “As I can see in conversations with my own young child, everything seems so local and immediate to them, and they pick up on the emotions and threats even if they can’t grasp that the news is showing something that happened in a different time and place. That means one change you can make is cutting out the TV news from the background in your home, and instead check in with other news sources or after young kids are in bed.”

Talk it Out

Talking to children about violent events in the news can seem like a daunting challenge, but there are ways parents can make their kids feel protected while also helping them understand the dangers of the world around them. “Parents and caregivers will want to check in, answer questions, and provide their own perspectives and assurances,” says Erica Scharrer, PhD, Chair of the Department of Communication at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “Older children and teens might hear about events from other sources, like social media or conversations with peers, but it’s a good idea to shield younger children from the news and answer any questions that arise with honesty, but without too much detail.” Regardless of age, Scharrer recommends that the most important things parents can do is assure children that they’re safe, stick to household routines, and be on the lookout for sleep disturbances, changes in behavior, or other signs of anxiety.

Even if you’ve assured young children that they’re safe, preschool age kids may still experience severe anxiety reactions. According Jeanne Funk Brockmyer, PhD, Distinguished Professor Emerita at the University of Toledo, there are two key guidelines for identifying reactions that warrant concern. “First, if a child demonstrates significant regression, for example a loss of skills such as toilet training, then that may signal a need for increased watchfulness,” says Brockmyer. “Second, marked anxiety behaviors such as frequent crying, nightmares, temper tantrums, resistance to bedtime, or separation problems may also indicate a worrisome reaction.” If persistent and unmanageable, these reactions may require a consultation with a healthcare provider or referral for professional counseling.

Talking openly with children about the content they’re consuming can provide a great learning experience for kids, but parents also need to put in the work to learn about the media their children are consuming and how they’re accessing it. “Parental discussions, which are interactive and supportive, can teach critical viewing skills that can mitigate the effects of exposure to violent media,” says Ed Donnerstein, PhD, Dean Emeritus at the University of Arizona. “Further, parents need to work on their own participation gap in their homes by becoming better educated about the many technologies their children are using.”

In addition to being available to ask questions, listen to concerns, and discuss how to process and cope with on screen violence, Case Western University Professor Daniel J. Flannery recommends that parents take a particularly proactive role in monitoring what their kids are watching. “Know your teen’s passwords, and randomly check their phone or iPad,” he suggests. “Use parental control apps to limit screen time or access to age inappropriate material. Write a contract together of expectations and consequences and sign it.”

Ready Player Two

Rather than simply condemning video games as a dangerous source of media violence, Villanova University Professor of Psychological and Brain Sciences Patrick Markey recommends that parents try playing their kids’ favorite games with them. “Today, video games (even violent ones) provide an opportunity for children to create real memories with their parents in a virtual playground,” Markey says. “Playing with our kids not only gives parents that chance to judge the violent content of games for themselves, but it also helps foster a connection between kids and parents.” Other scholars disagree, stating that using violent games to bond with children is a bad idea for any parent. They point out that parents wouldn’t smoke cigarettes or participate in other harmful activities with their kids just because the kids like it.

One Size Does Not Fit All

Children and teens can differ greatly in their reactions to media violence. Some may seem unaffected, while others may be restless or rough in their play or develop fears or nightmares. “If children have specific susceptibilities to media violence, parents know the best ways to reassure or calm down their kids,” says Patti Valkenburg, PhD, Distinguished University Professor of Youth, Media, and Society at the University of Amsterdam. “They may point at the unrealistic nature of violent heroes or episodes. They may stimulate their children to feel empathy with the victims of violence so they don’t imitate violent actions on their siblings. Already in 1946, Dr. Spock came with some reassuring advice to parents: ‘Trust yourself. You know more than you think you do.’”

Many times kids will act out scenes from violent movies or TV shows, but the motivation for this behavior can also vary greatly from child to child. “When your kid acts out scenes that you may disapprove of, ask yourself what’s actually going on,” says Jan Van den Bulck, PhD, DSc, University of Michigan’s Communication and Media Professor and Director of Quantitative Methods in the Social Sciences Program. “Some kids like being very active—is that what it is? Or is your kid practicing for the real world? The former is just play, but the latter means that your child was either negatively affected or that deeper-seated issues have surfaced in response to the media message.” Van den Bulck recommends parents focus less on the violence itself, and more on the message behind it. “Kids are clever, and they’ll learn from your reaction,” he says, “so see it as a teachable moment. Instead of a knee-jerk, authoritarian veto that makes violence the forbidden fruit, explain why you disapprove of the message. It may help your kid grow as a person without taking away the fun.”

—

Unfortunately, violence is a part of our world, and it’s impossible for parents to shield children from it entirely. However, with close monitoring, families can ensure that kids are consuming age-appropriate media and guard against the potentially damaging effects of frightening content when it’s inevitably encountered. Children will naturally be both curious and anxious in the face of violence, be it real or fictional, and it’s up to parents to provide context and reassurance.

About Children and Screens

Since its inception in 2013, Children and Screens: Institute of Digital Media and Child Development, has become one of the nation’s leading non-profit organizations dedicated to advancing and supporting interdisciplinary scientific research, enhancing human capital in the field, informing and educating the public, and advocating for sound public policy for child health and wellness. For more information, see www.childrenandscreens.com or write to info@childrenandscreens.com.